Gauls of Murthly

Thornie

Added on 19 June 2024

On the road out to the old A9 from Byres of Murthly, just past the sawmill on the right, there used to be a small farm: Gauls of Murthly. It had fields on both sides of the road. Today, the most noticeable feature by the roadside is a large clump of bamboo. The area behind that was once better known as Mill Dam. And immortalised by Sir John Everett Millais in one of a series of evocative landscapes he painted across the estate – ‘Lingering Autumn’ (1890).

A little way north of Gelly Cottage, formerly Three Mile House, the ancient pre-turnpike road from Perth to Dunkeld forked. The right-hand cart track then headed north-east past Colrie to the ferry point on the Tay known as Boat of Murthly. The left-hand one continued, now in the lee of Birnam Hill, down to Dunkeld via another ferry, at Inver. Down between Gauls of Murthly and Byres of Murthly.

A little way north of Gelly Cottage, formerly Three Mile House, the ancient pre-turnpike road from Perth to Dunkeld forked. The right-hand cart track then headed north-east past Colrie to the ferry point on the Tay known as Boat of Murthly. The left-hand one continued, now in the lee of Birnam Hill, down to Dunkeld via another ferry, at Inver. Down between Gauls of Murthly and Byres of Murthly.

Note that in those few sentences we name check the estate’s most prominent ‘X of Y’ combinations:

Byres – possibly an early equivalent to mains or home farm;

Boat – the ferry closest to the castle which, although public, was there primarily because the Stewarts then had extensive holdings on the north side of the river; and

Gauls – the odd one out, not seemingly a description of function. And not an easy name to parse, as we shall see.

The commonest Scottish ‘X of Y’ place-name combinations, in which a generic term precedes a qualifying element linked by the preposition of, are variations to do with water: Burn of Vat, Burn of Birse, Burn of Sorrow, Boat of Garten etc. Nary a one in Perthshire, by the way. But the combinations occur in other ways: Bullers of Buchan, Braes o’ Fosse, Mains of Murthly etc. (The latter confuses the issue somewhat as it has nothing to do with ‘our’ Murthly. It’s a steading above the distillery on the edge of Aberfeldy.)

Gauls of Murthly may be unusual, but it is neither peculiar nor unique.

Before examining the potential origins of this place-name it is worth having a look at its place on the estate.

Murthly pre-railway

Murthly today centres on the crossroads at the junction of the B9099 and the road to Kinclaven. Where once again there is a bar and restaurant, Uisge. Close by are the village hall, level crossing, and a housing estate, Druids Park. A little way down the road the prominent landmarks are Wilks Garage and the shop/post office. And there’s the primary school up at Ardoch, oddly at the edge of the village (because it was shared with Airntully, from a time when every kid walked to school regardless of the weather).

People remember village history, if a bit vaguely on dates. That Murthly once had an inn (burned down in 1928), a railway station (closed 1966), a lunatic asylum (closed in 1986), and a church (deconsecrated in 1986). If you stand at the crossroads and look at all the houses around, then cast your mind’s eye along Kinclaven Road right to the last house, and similarly down the B9099 to the bungalow on the other side of the post office . . . none of them existed before 1856.

Yet the Stewarts acquired Murthly Castle and the estate, in a dodgy deal, as far back as 1615. (From the Abercrombies, a recusant family: Catholics still in a newly Protestant, virulently anti-papist Scotland.) Between then and the coming of the railway in 1856 their attention and focus was elsewhere. On the farms of Tathyhill, Pittensorn, Hillhead, Byres, and across what is now the old A9 to the even more productive fermtouns of Meikle, Nether and Upper Obney, and another half dozen smaller farms close by. As shown in a clip below from James Stobie’s map of The Counties of Perth and Clackmannan of 1783, where the fermtouns in the “Opnies” are prominent.

In the middle to late 18th century, the busiest part of Murthly estate was Colrie, near Byres. Because of its three mills: two for grinding meal, one for lint. Today all that remains is Colrey Lodge nestled by the A9 on the Pittensorn Road. And a neglected mill pond. (The spelling has changed over the centuries.)

In the middle to late 18th century, the busiest part of Murthly estate was Colrie, near Byres. Because of its three mills: two for grinding meal, one for lint. Today all that remains is Colrey Lodge nestled by the A9 on the Pittensorn Road. And a neglected mill pond. (The spelling has changed over the centuries.)

Back in the day, Gauls of Murthly was much more in the centre of things. However, we do not know how or when it got its name.

It may be we should look for its derivation in the old Gall-Ghaidheil nomenclature. Alison Grant in an article for ‘The Bottle Imp’ (Issue 10) tells us that: “ The Gaelic place-name gall means ‘stranger, foreigner’, and occurs in Scottish place-names including Achingall ‘field of the strangers’ (East Lothian), Rubha nan Gall ‘point of the strangers’ (Mull), Cnoc nan Gall ‘hill of the strangers’

(Colonsay), Allt nan Gall ‘stream of the strangers’ (Sutherland), Inchgall ‘isle of

the strangers’ (Fife), Barr nan Gall ‘summit of the strangers’ (Argyllshire) and Camusnagaul ‘bay of the strangers’ (Wester Ross).”

In many cases said strangers were Viking settlers. Who left their mark down the west coast from Fingal’s Cave to Galloway and across the Irish Sea. In fact, two kinds of strangers: Fair (Norwegians) which comes through in names - fionn gall/Fingal; and dark (Danes) - dubh gall/Dougal. There were also later incomers, known as Gall Bhreathnach/stranger-Britons.

There are three instances of Gall/Gaul in place-names locally, within four miles of each other.

One is Galbrydistoun, which Dr Simon Taylor, leading expert in Scottish Place-Names studies, suggests is early medieval. “It seems to contain the personal name Galbraith [Gall-Bhreathnach "stranger-Briton,"] with the Scots habitative element toun, not introduced north of the Forth until the late 12th century.” Today the area is known as Bradystone.

The other two are different to Galbrydistoun but akin in topography. The other Gall, by the way, lies on the edge of Bankfoot between the junction with the road to Murthly and Taste of Perthshire.

There is no evidence of Norse settlement there or on Murthly estate, however. Invasion and a stay well beyond welcome in and around Dunkeld in the late 9th century, yes. But no archaeological evidence of roots being put down.

Dating Gauls Farm

The earliest evidence we have of Gauls of Murthly is an undated, but from its context clearly 18th century map: “Plan of Farm of Byres”. (Murthly & Strathbraan Estates archives.) Bordering this coloured plan is a blank area named as Gauls Farm. The earliest map of Gauls of Murthly itself is in the folio of estate plans published in 1825. (Murthly & Strathbraan Estates archives.) Interestingly, the main feature, the Cyrano schnoz of the farm, is a large body of water: emphatically marked ‘Gauls’. (The steading is also named.) This is repeated in “Plan of the Baronies of Grandtully, Murthly and Strathbraan” c. 1830. (Part of the Grandtully Muniments on loan to the National Records of Scotland.) And again, in “Plan of the Farm of Byres and Kingswood” c. 1856 (Murthly & Strathbraan Estates archives), where it is given as ‘Gauls Loch’.

The farm was bounded to the north by the turnpike road from Perth to Dunkeld (now the old A9); to the west it marched with the lands of Dalpowie at Birnam Burn; and to the south, Byres of Murthly. The largest acreage of the farm lay to the south and east, marching with another estate farm, Muirlands. In this section the grass parks were dominated by scrub, tussocks and gorse. Ground not yet fully wrenched from the Muir of Thorn, much of it bog, with a massive 10 acre spread of open water and shrub covered islets. In the estate plans of 1825 Byres farm is shown as having 100 acres. By contrast, neighbouring Gauls had only 79 acres, and this difference is made starker yet by their relative rental values: £165 per annum as opposed to £75. Gauls only declined in value over the years. By 1885, it had all but disappeared as an independent farm. Byres farm grew though, but in the opposite direction, encompassing Kingswood.

The farm was bounded to the north by the turnpike road from Perth to Dunkeld (now the old A9); to the west it marched with the lands of Dalpowie at Birnam Burn; and to the south, Byres of Murthly. The largest acreage of the farm lay to the south and east, marching with another estate farm, Muirlands. In this section the grass parks were dominated by scrub, tussocks and gorse. Ground not yet fully wrenched from the Muir of Thorn, much of it bog, with a massive 10 acre spread of open water and shrub covered islets. In the estate plans of 1825 Byres farm is shown as having 100 acres. By contrast, neighbouring Gauls had only 79 acres, and this difference is made starker yet by their relative rental values: £165 per annum as opposed to £75. Gauls only declined in value over the years. By 1885, it had all but disappeared as an independent farm. Byres farm grew though, but in the opposite direction, encompassing Kingswood.

A possible etymology?

On the Dictionaries of the Scots Language website there is a clue to the origin of the name . . . ‘Gaul’ is a variant of Gal n. the bog myrtle, Myrica gale. First noted in print in 1726 by a botanist, W. Macfarlane. Then in James Boswell’s Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785): “The sweet-smelling plant which the Highlanders call gaul.” Back in the day young bucks would tuck a pungent sprig in their bonnets when courting. Trust Boswell to fasten on that. In traditional folklore bog myrtle has also long been considered a good repellent against insects such as the midge (Culicoides impunctatus) and this has recently been confirmed through scientific tests of the oil extracted from the plant. (According to Trees for Life.) An armful gathered into your tent might make all the difference . . . If you have no stomach for the modern alternative, Avon’s Skin So Soft aka granny-juice.

However, as the name suggests, bog myrtle thrives on acidic, none too solid peaty ground. A tenant farmer might not be so easily won over to it growing profusely on his small farm. Old farmers know the term as describing a watery, boggy place. It seems likely that Gauls of Murthly was so called because it was ill-favoured land.

Its major feature, however, has been transformed over the years into Mill Dam. Fed from Stairdam below Birnam Hill, it became an important power source via a system of sluices and a lade that turned the big wheel at Murthly sawmill, and was channelled to another pond above Colrie to turn the wheels of three more mills.

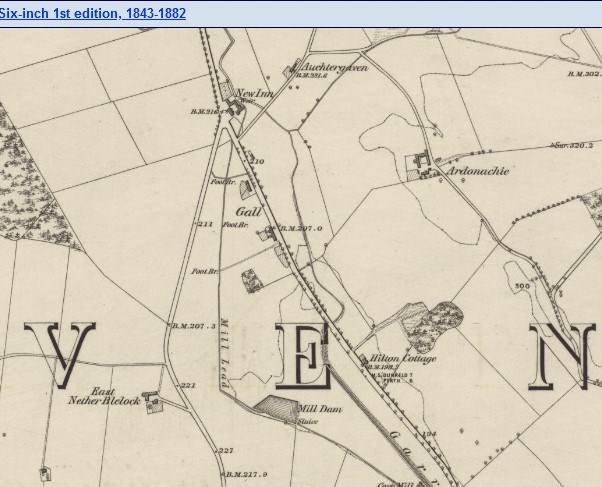

The other ground known as Gall/Gauls, just south of Bankfoot, we know from the first edition OS map at 6” to the mile (from an 1864 survey) as a triangular area : ’Gall’.

Significantly, the land includes a body of water, Mill Dam, and is bisected by a lade. In later editions, although the water has been drained, memory of it and the boggy nature of the ground persists to the north and south of the B869, which are shown as Upper Gauls and Lower Gauls.

Significantly, the land includes a body of water, Mill Dam, and is bisected by a lade. In later editions, although the water has been drained, memory of it and the boggy nature of the ground persists to the north and south of the B869, which are shown as Upper Gauls and Lower Gauls.

Remember the commonest ‘X of Y’ place-name combinations? Water related. I may have to rethink my assertion there is nary a one in Perthshire.

Illustrations:

The Counties of Perth & Clackmannan

by James Stobie, 1783

(Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland)

Gauls Loch extract from Plans of Airntully & Murthly estates (Courtesy of Murthly & Strathbraan estates)

Gall of Bankfoot from OS 6": 1 mile, 1st ed. 1864 (Courtesy of the national Library of Scotland)