Murthly Ha-Ha

Added on 31 March 2021

The planning application for four poultry rearing sheds and associated works on farm land just to the southwest of Murthly village was dismissed in early January. Almost at the top (#2) of the accepted objections was one made by Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust (PKHT).

PKHT particularly feared for the ha-ha feature on the site: “The full importance, function and evolution of these designed landscapes is not well understood due to lack of study and field work to date”.1 Adding they should be protected and preserved: particularly because of their close association with the Murthly Castle Designed Landscape.

PKHT particularly feared for the ha-ha feature on the site: “The full importance, function and evolution of these designed landscapes is not well understood due to lack of study and field work to date”.1 Adding they should be protected and preserved: particularly because of their close association with the Murthly Castle Designed Landscape.

A ha-ha is a sunken fence that removes the need for dykes or post and wire fences to corral livestock thereby allowing open, uninterrupted views across a landscape. (A section of ha-ha closest to the disputed site is on the left. Collie for scale.)

They are most typically associated with stately homes. The concept is French and was first described in 1709 by Dezallier d’Argenville in his La Theorie et la Practique du Jardinage (The Theory and Practice of Gardening). It was quickly taken up in England, and ha-has first appeared there in the gardens and parks of Stowe, in Buckinghamshire, about 1720.2 To gauge the depth of impression they made with the public then, think back to the first sunset you saw from a rooftop infinity pool. You may be blasé now, but honestly? Wasn’t that a “Wow!”

Just as quickly it became a ubiquitous feature, almost to the point of cliche. Something Jane Austen picked up on in Mansfield Park (1814) when she had Mary Crawford exclaim, “I have looked across the ha-ha til I am weary. I must go and look through that iron gate at the same view.”

There is a question mark as to when the Murthly ha-has were constructed. If, fashionably, in the 18th century then the inspiration for them was not Stewart, but Mackenzie. If post 1820, they may no longer have been fashionable, but they were certainly a more expensive way of controlling stock. Arguably, they would not have added much value to the landscape: the parks have a mixture of sunken and raised dykes. Their impact as designed landscape comes from their irregularity of shape lying amid those impressive shelter belts: and their size. This article is an attempt, through sifting available documentary evidence and by walking the ground, to offer a tentative timeline. Evidence seen in the field suggests one scenario: which is contradicted by a couple of estate maps.

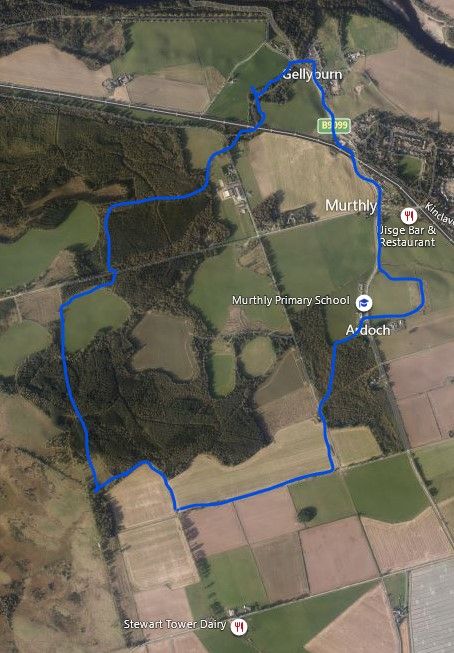

Throughout most of the 18th century a key portion of today’s estate stretching south from the Gellyburn up to Ardoch (mainly on the school side of the B9099), and west encompassing the farms of Bradyston and Douglasfield, was actually the lands of Cowbrydieston or Culbrydieston. (As outlined in blue on the left.) John Mackenzie, 1st of Delvine, an advocate in Edinburgh, acquired the barony of Delvine and Cowbrydieston in 1704. He had three sons of whom Alexander and the youngest, John, followed him into the legal profession. All three were Writers to the Signet, and each served in turn as Principal Clerk of Session, that is, as chief administrator to Scotland’s supreme civil court, the Court of Session. (Sir Walter Scott would also hold this office from 1806.) Alexander’s grandson, Alexander Muir, followed in the family tradition. In some respects, the Mackenzie family were to Scotland’s legal profession what the Stevensons were to civil engineering. But, y’know, a phrase like “The Lighthouse Stevensons” will cleik wae the publik more readily than “Torts & Testament Mackenzies”.

Throughout most of the 18th century a key portion of today’s estate stretching south from the Gellyburn up to Ardoch (mainly on the school side of the B9099), and west encompassing the farms of Bradyston and Douglasfield, was actually the lands of Cowbrydieston or Culbrydieston. (As outlined in blue on the left.) John Mackenzie, 1st of Delvine, an advocate in Edinburgh, acquired the barony of Delvine and Cowbrydieston in 1704. He had three sons of whom Alexander and the youngest, John, followed him into the legal profession. All three were Writers to the Signet, and each served in turn as Principal Clerk of Session, that is, as chief administrator to Scotland’s supreme civil court, the Court of Session. (Sir Walter Scott would also hold this office from 1806.) Alexander’s grandson, Alexander Muir, followed in the family tradition. In some respects, the Mackenzie family were to Scotland’s legal profession what the Stevensons were to civil engineering. But, y’know, a phrase like “The Lighthouse Stevensons” will cleik wae the publik more readily than “Torts & Testament Mackenzies”.

John Mackenzie, 2nd of Delvine (1709 - 1778) bought the estates from his older brother, Kenneth, in the 1740s. Although he had a busy practice, and acted as agent for the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Atholl Dukes, advising them on legal and financial matters, he was determined to make the best of his acquisitions. Mackenzie of Delvine was an Improver.

TC Smout is very clear that the “agricultural revolution” in Scotland was patchy, spasmodic, took a long time to catch on: it was not carried through on a storm of enthusiasm. He dates the start from 1720 with the inception of The Honourable Society of Improvers, in Edinburgh, “as a propaganda effort to spread knowledge of the new farming”.3 However, even by 1780 the Improver was still the exception. Mackenzie then was in the first wave of those who sought to introduce new methods of husbandry, new crops, and better farmsteads. His interest was mostly financial, whereas for others it might equally be a cultural imperative. As Smout contends was the case, for example, with Lord Cockburn, who was “doing his bit for Scotland, his way of dragging her into the Britain of the eighteenth century.” 4

Mackenzie was not backward in advising one client, John Murray of Strowan, 3rd Duke of Atholl, to raise rents: “Your Grace would have little occasion to beg for your self were you pleased to permit those whom you pay for prying into your private affairs to try our skill on a moderate rise of your rents.” He was convinced that, “while you continue them precisely on the old establishment [your tenants] will never change their old modes of farming or rather of scratching the ground & so starve themselves and their beasts for life.”5 Mackenzie’s correspondence is salted with stinging comments in this vein. Tenants lacking his enthusiasm for the new ways were disparaged for wanting “nothing better than the poverty and dirt their fathers left them in.”6 We could propose some sense of mission here . . . were it not for Mackenzie’s statement that he simply desired to “grow rich by finding proper returns from our extensive Improvements.”7

His improvements to Delvine, and the creation of Spittalfield as a planned village from 1762, are covered well in Jim Black’s The Heart of the Stormont: Past Times in Spittalfield, Caputh and Round About (Abertay Historical Society #61, 2020). We are concerned here with those carried through in West Stormont, in the area that would eventually be known as New Delvine. Which pre-occupied him almost from the beginning of his tenure.

In 1744, Mackenzie unveiled an elaborate plan for bringing the Muir of Thorn into cultivation. He would “beat his betters” (a veiled swipe at his neighbours, Sir John Stewart, and his client, the Duke of Atholl?) in putting “a decent face on that Mure which was not meant to lye in Dark heather for the purpose of Scalping the surface to the Day of Judgement.”8 Said “scalping” being cutting turf for roofing houses, which Mackenzie saw as detrimental to the soil.

Let us not for a minute underestimate the scope and scale of this ambition. At the time the Muir of Thorn was this huge “blasted heath” lying across parts of three parishes; Little Dunkeld, Auchtergaven, and Kinclaven. (Much more extensive then than indicated on the 1st ed. OS map.) To someone like Mackenzie it could have seemed a clenched and threatening fist. Most of his 350 acres of Cowbrydieston lay in its grasp; yet only about a thumb and forefinger’s worth of the total area. It would prove to be hard back-breaking labour; draining bogs; tearing up brush wood; and carting off stones – even with liberal use of black powder to blow up the boulders.

Mackenzie began by giving William Dow a 19-year lease for as much muirland as he could turn to arable ground. He advanced this pioneer 1000 merks (£667 Scots) and 12 ‘couples’ of good timbers for houses. Dow’s challenge was to bring four acres of muir into infield arable each year. He would be absolved rent for five years, thereafter paying 100 merks (£67 Scots) annually for the next five, with the rent rising (in line with productivity, it was hoped/assumed) to £100 Scots a year for the remaining nine years of the tack. Can you discern the lawyer in this arrangement? Well, should Dow tak the craw road during the first five years his “aforesaids” (heirs) would be obliged to repay 800 of the 1000 merks advanced: 500 merks if they mourned his demise any time in years five to ten. Nothing would be reclaimed, however, if the sorrowful event occurred during the final nine years. So long as at least 30 acres had been brought into cultivation in the first ten years.

Dow shook hands on this deal (and might have had pause to count his fingers thereafter). Unfortunately, Mackenzie’s grand scheme came to nothing: Dow indeed took the crow road, dying in 1750. His heirs gave up the lease soon after. The lawyer tried again, with the brothers, John and Thomas Neill, who took over in 1753. Only to renounce four years later as their improvements were not producing enough to pay the rent.9

Mackenzie re-grouped and tried again in 1769. More alive now to best husbandry practice in England, with new crops, rotations and implements, he resolved that the Muir should be “substantially” enclosed, and proper steadings erected. Ditching and dyking began then and continued until 1773. A new two storey “Beau Window” house, slated and harled, was planned, intended to be “a compleat farm after the English form.” This, along with a barn and byre, enclosures and plantings, was completed by 1773. It was entered in the account book as ‘New Delvine’. At a cost of £137 6/9d Scots.10

When “this new farm” was completed Mackenzie imported an English farmer, William Wright. He was subsidised to begin with, but Mackenzie changed his tune by the end of the year, saying that he would get no more “so that he might work harder.” Which actually paid off. By the middle of 1774, Mackenzie was much happier with Wright: he had indeed “dresst his Mure with very Uncommon Neatness, His House is Clean, his access Sweet, Decent & Cleanly & his fields properly Laid out & fenced in & Carry a thriving appearance though situated in an Uncultivated Heath.”11

John Mackenzie, 2nd of Delvine died in 1778. He was eulogised in the First Statistical Account for Caputh as “without exception, the first improver of this country.”12 Similarly, Rev. Robertson’s account for Little Dunkeld drew attention to “a very public spirited gentleman (who) 25 years ago, made out a good large farm on a moor at the east end of the parish, which he accommodated with substantial elegant farmhouses [New Delvine and Walton] and out-houses, that promise to turn to good account.”13 He left everything, all goods and gear, forests, lands and estate of Delvine, in life rent to his widow, Cecilia Renton.14Thereafter, as they were childless, it would all go to his great-nephew Alexander Muir (who added ‘Mackenzie’ to his name when Cecilia died in 1803. He was knighted in 1805.).

During John 2nd’s ownership, 642 roods (3,626m) of dyking was completed between 1769 - 1773. Much of this, being a good neighbour, was along the line where his land marched with Murthly to the south, east and west: the Gellyburn formed the northern boundary. In 1779, dyking extending to a further 385 roods (2,174m) was built in the West Muir of Thorn: 598 roods (3,379m) in the eastern part, by then known as New Delvine. (It seems that Alexander actively managed the estates for Cecilia and continued with the improvements.) 15

What kind of dyking? Are both sunken and raised dykes given the same name in the accounts? If so, then we need to know the rate per rood, for one type is considerably more labour intensive. But until the National Library’s doors are open once again . . .

In May 1819, Sir George Stewart of Grandtully and Murthly received a letter from George Condie, the family solicitor in Perth and his “man of business”. Condie had got wind that Sir Alexander Muir Mackenzie might be of a mind to sell New Delvine, and urged him to pursue this, “if fair and equal terms can be had.” He also threw in that Mackenzie might entail his estates, “after which it could not be got at all.”16 Wait . . . Have we just come across a FOMO hook in a 19th century letter? (FOMO: fear of missing out. One of the sales conversion techniques of 21st century marketing.)

Sir George duly made his offer, which Sir Alexander countered, but it seems both parties really wanted a deal, for an agreement was in place by September. On the 17th, Richard Mackenzie WS wrote to Condie that he was sending “by coach” the title deeds of the lands of New Delvine. The deal was settled on a mixture of cash and excambion: Sir George exchanged some of his land on the north of the Tay, and included the island opposite Easter Burnbane, “contiguous with Delvine”. He took possession that Martinmas of two farms (New Delvine & Walton) five pendicles, and Gellyburn Quarry, along with plantations of fir. The net rentable value was £235 8/1d.17

Which now brings us to the question: who did what? Who was responsible for building the ha-has?

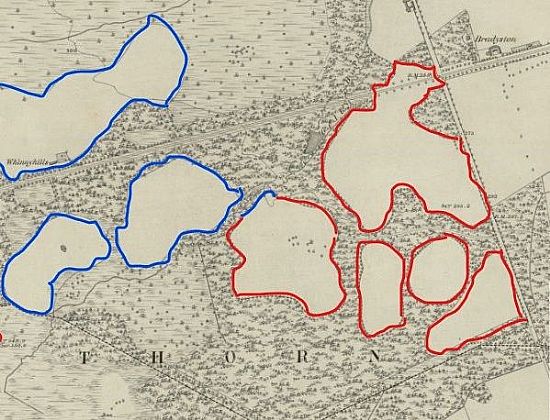

There are approximately 4.5km of sunken dykes containing the parks formerly known as New Delvine. These are outlined in red to the left: Blue outlines denote Murthly parks, which all have raised stone dykes. Note there is one park that is mostly red, but with a section of blue indicating where the ha-ha gives way to a 4’ raised dyke.

There are approximately 4.5km of sunken dykes containing the parks formerly known as New Delvine. These are outlined in red to the left: Blue outlines denote Murthly parks, which all have raised stone dykes. Note there is one park that is mostly red, but with a section of blue indicating where the ha-ha gives way to a 4’ raised dyke.

Entrances to Murthly parks throughout the estate are marked with twin conical pillars of dressed stone. It’s a Stewart signature, if you like. However, gateways to New Delvine parks are not so prominently marked, save in one instance. The first image below shows the entrance to the park which used to hold the Walton (Welltown) farmstead.

At the western edge, where the sunken dykes gave way to raised walls are the first Murthly pillars. (Below) Beyond that gateway lies the Gellyburn and the western march of New Delvine with Murthly. Thus, the gateway is on the ‘wrong’ side of the burn, but for practical purposes you would not put it anywhere else. And after 1819 when everything there came into Stewart ownership, what would it matter?

At the western edge, where the sunken dykes gave way to raised walls are the first Murthly pillars. (Below) Beyond that gateway lies the Gellyburn and the western march of New Delvine with Murthly. Thus, the gateway is on the ‘wrong’ side of the burn, but for practical purposes you would not put it anywhere else. And after 1819 when everything there came into Stewart ownership, what would it matter?

The estate maps of 1784 and 1825 flatly contradict this reading. That of 1784 was prepared by Adam Kay, of whom nothing is known, and illustrates a boundary dispute between Sir John Stewart and Widow Mackenzie. It’s a strange piece of cartography, with no scale, no ‘up or down’ (in fact, it can, needs to be read from four directions) but wonderfully detailed. The extract below shows rectangular fields: no dykes.

The estate maps of 1784 and 1825 flatly contradict this reading. That of 1784 was prepared by Adam Kay, of whom nothing is known, and illustrates a boundary dispute between Sir John Stewart and Widow Mackenzie. It’s a strange piece of cartography, with no scale, no ‘up or down’ (in fact, it can, needs to be read from four directions) but wonderfully detailed. The extract below shows rectangular fields: no dykes.

The 1825 map is part of a folio of plans covering all of Murthly and Airntully. Surveyed by James Chalmers, Sir George’s new factor, it shows that not a lot had changed since 1784. Muir Mackenzie had not prioritized New Delvine in those 25 years. A few more tree belts, but the same rectangular look overall (although with a hint of re-shaping that might be the beginning of the parks as they are today). And, to the west, a huge expanse of muir still to be conquered.

The 1825 map is part of a folio of plans covering all of Murthly and Airntully. Surveyed by James Chalmers, Sir George’s new factor, it shows that not a lot had changed since 1784. Muir Mackenzie had not prioritized New Delvine in those 25 years. A few more tree belts, but the same rectangular look overall (although with a hint of re-shaping that might be the beginning of the parks as they are today). And, to the west, a huge expanse of muir still to be conquered.

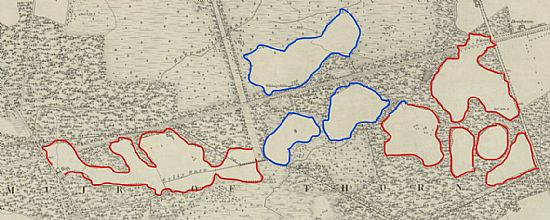

In the final image the parks outlined in blue, with raised dykes, are in fact book-ended by parks enclosed by ha-has (outlined in red). The Gelly Parks to the west of the muir add approximately 5km to the total. (The approximation arising from their being sliced through by the new A9 in the 70s.) These were created by the Stewarts. Evidence on the ground, coupled with the estate maps, thus supports the idea that the sunken dyke features are Stewart, not Mackenzie.

In the final image the parks outlined in blue, with raised dykes, are in fact book-ended by parks enclosed by ha-has (outlined in red). The Gelly Parks to the west of the muir add approximately 5km to the total. (The approximation arising from their being sliced through by the new A9 in the 70s.) These were created by the Stewarts. Evidence on the ground, coupled with the estate maps, thus supports the idea that the sunken dyke features are Stewart, not Mackenzie.

Which takes nothing away from Mackenzie of Delvine’s pioneering work to reclaim and enclose the Muir of Thorn. In improving New Delvine he began to prise open that gnarled fist.

Notes & Sources:

- Sophie Nicol, Historic Environment Officer, PKHT

- “What is a ha-ha”, Geraldine Porter, NTS. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/what-is-a-ha-ha

- “A History of the Scottish People 1560 – 1830”, T.C.Smout, p 296 (Collins, London, 1969)

- Ibid, p293

- “Living in Atholl 1685 - 1785”, Leah Leneman, p 25 (Edinburgh University Press, 1985)

- “The Heart of the Stormont”, Jim Black,p121 (Abertay Historical Society, 2020)

- Allan Brown, MA Thesis relating to Delvine Estate in the 18th century: Edinburgh University 1966. (Thanks to Jim Brown for supplying an extract.)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Original Statistical Account [OSA], Clunie 1791

- OSA, Little Dunkeld, 1792

- Edinburgh Commissary Court.

- Brown

- Grandtully Muniments, National Records of Scotland [NRS], Letters 1818-1819

- Ibid