The Dandy Fechters - Part 2

Added on 22 September 2020

Late in 1816, Richard Ryder, veteran of Waterloo, five other major battles and countless skirmishes, fell victim to “the peace dividend”. Parliament’s necessary, but still ruthless determination to save further military expenditure saw thousands of veterans discarded.

The troopers of the 15th had seen what had happened in other regiments months earlier. Pension less, many veterans, who counted themselves lucky, were swept into the ‘dark satanic mills’ or the mines; the less fortunate often ended begging in the streets, or in the workhouse. It may have been an impetuous decision on William’s part but more likely that he had prepared for this, for he immediately hired Richard as his personal servant.

William remained with the 15th Hussars, then stationed in the north of England to support magistrates when local yeomanry proved insufficient to the task of suppressing dissent. We do not know how many times he and Richard managed to visit Murthly in the next three years. Clearly, often enough for Richard to form an attachment with Anne Logie, one of the servants. As recounted in Part 1 Richard and Anne married in February 1819. He was 38 and she had just turned 28. That their first child, Ann did not come along until March 1824 suggests Richard may not have been around much in the first couple of years. (An earlier, unsuccessful pregnancy is always a possibility, of course, but the other daughters were similarly spaced, Helen in 1827 and Jean in 1833.)

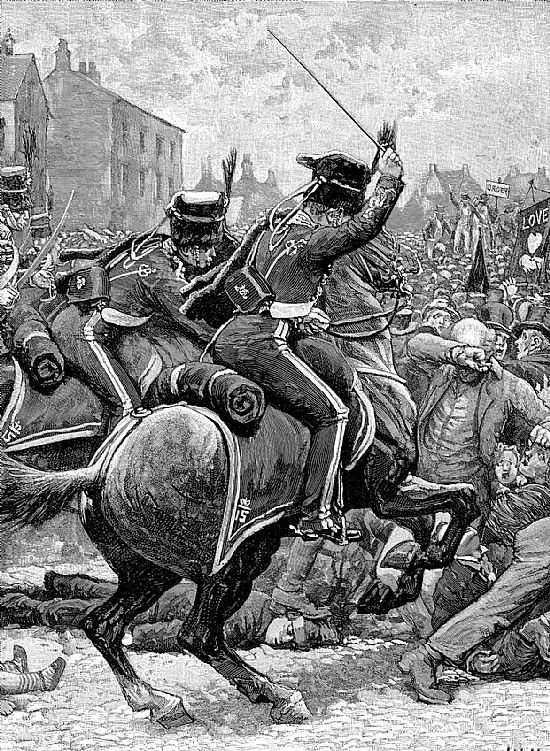

It seems likely Richard was with Lieutenant William Stewart in August 1819, at Hulme Barracks in Manchester. On the 16th, a Sunday, a great crowd, possibly as many as 60,000 men, women and children, many in their church going best, and accompanied by several bands, gathered in a vast open are known as St. Peter’s Fields. With banners and flags flying they were there for a peaceful rally calling for political reform, principally universal suffrage, and to hear several Radical speakers, chief among them the famed orator, Henry Hunt, and the leader of the Manchester Female Reform Group, Mary Fildes. Anticipating trouble, Manchester’s magistrates had called up 120 members of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry to arrest the speakers. As a little reserve, Colonel George L’Estrange of the 31st Foot, in overall command of military forces that day, had previously agreed to have six troops of the 15th Hussars, seven companies from the 31st and 88th Foot, 400 members of the Cheshire Yeomanry, and a detachment of Royal Horse Artillery with two six pounder cannons standing by. A combined force estimated at over 1,000 men. Lt. Colonel Dalrymple, who had lost a leg at Waterloo, commanded the Hussars.

The regimental history is terse in its account of what happened that afternoon: “The regiment was employed in suppressing the illegal assemblages of the people in Manchester (gathered) under the pretence of petitioning for a radical reform in the Commons House of Parliament.” Terse, and disingenuous in suggesting the citizens had some ulterior motive. That day’s protest was part of a national movement. By the time, 1841, when Richard Cannon was re-writing the regiment’s history that “pretended petitioning” had already resulted in passage of the Reform Act of 1832.

L’Estrange’s report to his chief, Major General Sir John Byng, written that very day, was also rather short: “I have great regret in stating that some of the unfortunate people who attended this meeting have suffered from sabre wounds, and many from the pressure of the crowd. One of the Manchester yeomanry, if not dead, lies without hope of recovery; it is understood he was struck with a stone. One of the special constables has been killed.”

Lt. Sir William Joliffe, then just 19 but leading a troop of hussars, penned his account of what happened. The Manchester Yeomanry, mounted, were ordered by the magistrates to arrest Hunt and Fildes, but made a hash of it, panicked and started lashing out with their sabres. L’Estrange ordered the 15th to help. “The Hussars drove the people forward with the flats of their swords, but sometimes, as is almost inevitably the case when men are placed in such situations, the edge was used, both by the Hussars and, as I have heard of, by the Yeomen also . . . I still consider that it rebounds to the humane forbearance of the men of the 15th that more wounds were not received, when the vast numbers are taken into consideration.”

Lt. Sir William Joliffe, then just 19 but leading a troop of hussars, penned his account of what happened. The Manchester Yeomanry, mounted, were ordered by the magistrates to arrest Hunt and Fildes, but made a hash of it, panicked and started lashing out with their sabres. L’Estrange ordered the 15th to help. “The Hussars drove the people forward with the flats of their swords, but sometimes, as is almost inevitably the case when men are placed in such situations, the edge was used, both by the Hussars and, as I have heard of, by the Yeomen also . . . I still consider that it rebounds to the humane forbearance of the men of the 15th that more wounds were not received, when the vast numbers are taken into consideration.”

Yet many hundreds of civilians were sabred and trampled in the melee. Accounts of what happened have always been muddled, but more recent investigations around the 200th anniversary of the ‘massacre’ now suggest that 18 civilians were killed, including four women and a child, and 700 seriously injured.

Heroes to zeroes, in an afternoon. The term “Peterloo” was coined by the people of Manchester to ridicule the 15th, who up to that point had been seen as the dashing heroes of Waterloo. One persistent story, however, is that an un-named officer of the 15th attempted to strike up the swords of the yeomanry crying, “For shame, gentlemen: what are you about? The people cannot get away.” Persisting, perhaps, because emphasising that someone’s conscience was at work condemns the yeomanry still further.

We have no documentary evidence of William’s involvement that day. However, given the social and political unrest across the north of England in the summer of 1819 it is likely that the 15th would have been kept at full strength. Did Peterloo sicken him? Was it the final straw? He was still not quite 25, still the restless adventurer who had joined the King’s Hussars to escape the boredom of garrison duty with the Guards. We do know that William began the process of extricating himself from the regiment later in the year. His first move was to draw upon Sir George’s bank of influence with a neighbour, Thomas Graham, first Baron of Lynedoch, Wellington’s second in command during the Peninsula Campaign. Graham was persuaded to write to his friend Major General Sir Herbert Taylor putting forward a case for William’s promotion to captain. Taylor had no direct link with the 15th, but he was incredibly well connected and during his career served as Private Secretary successively to Kings George III, George IV and William IV. William duly received his captaincy in June 1820, and shortly afterwards retired on half pay, while reserving the right to sell his commission at a later date.

Captain Stewart kept rakish company in London for a time in the 1820s, making use of the family’s town house at 77 Eaton Place. (Now subdivided into apartments, Flat 2 recently sold for a sum in excess of £2 million.) He also made the Grand Tour, but instead of the hackneyed Paris- Florence-Rome itinerary he followed his hero, Byron’s route through Greece and Turkey. Richard was home often enough, however, to continue building his own family. Rather surprisingly, William too had a son. Seemingly from nowhere. In 1830 he had a brief dalliance with a local servant girl, Christian Battersby, who became pregnant. Their son, William George was born in February 1831. He was baptised in St George’s Chapel in Edinburgh. (Although his mother’s name is given as Christian Stewart on the certificate the word “spouse” is scratched out.) William set mother and son up in a flat there, but never lived with them. The following year he removed himself further still from any threat of a domestic arrangement, by sailing to America.

Richard did not accompany William on his American adventures, neither in 1832 nor 1842. It is presumed he remained in Murthly as a groom and coachman. As is so often the case with servants and others working on the estate he rather drops from sight for long periods. We know he, Anne and the children lived comfortably at Newtyle Cottage (now Rose Cottage, the one closest to the castle) but possibly only from around 1838, when William inherited the baronetcy, estates, and his brother’s enormous money pit, the New Castle. William had returned from the States with buffalo, trophies, his own artist, Alfred Jacob Miller, and a new servant/companion, Antoine Clement.

In 1847, the War Department issued a Military General Service Medal for all who had served in the British Army between 1793 and 1840 – and were still alive to apply for it. Twenty-one clasps were also available for service during the Peninsula Campaign and battles leading up to Waterloo. Here was one last chance for the old hussars, William and Richard, to celebrate. Richard had the better bragging rights: he was entitled to add clasps for Sahagun, Salamanca, Vittoria, Orthez and Toulouse. William for just the latter two battles. Both already had their Waterloo Medal, of course, 40,000 of which were struck for the survivors, notably the first medal issued to rank and file as well as officers. In another first, the Royal Mint took advantage of new technology to stamp an individual’s name, rank, and unit on the edge of each one. William’s reads, “Lieut. W. Stewart – 15th Hussars.”

In 1847, the War Department issued a Military General Service Medal for all who had served in the British Army between 1793 and 1840 – and were still alive to apply for it. Twenty-one clasps were also available for service during the Peninsula Campaign and battles leading up to Waterloo. Here was one last chance for the old hussars, William and Richard, to celebrate. Richard had the better bragging rights: he was entitled to add clasps for Sahagun, Salamanca, Vittoria, Orthez and Toulouse. William for just the latter two battles. Both already had their Waterloo Medal, of course, 40,000 of which were struck for the survivors, notably the first medal issued to rank and file as well as officers. In another first, the Royal Mint took advantage of new technology to stamp an individual’s name, rank, and unit on the edge of each one. William’s reads, “Lieut. W. Stewart – 15th Hussars.”

Richard had one last career change around this time: He was given tenancy of the inn at Kingswood, holding it until 1856.

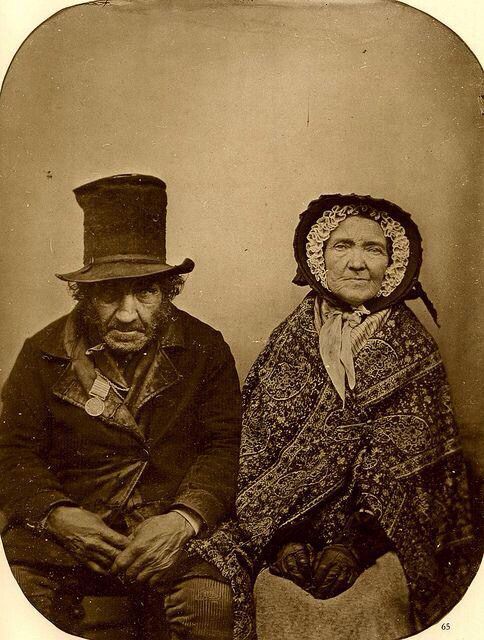

Thereafter, now in his seventies, he slipped quietly into retirement. (The photo here is not Richard and Anne, but of a Waterloo veteran and his wife of similar age.) Anne predeceased him. Richard eventually moved to live with his daughter Helen and her husband John Pullar, at their farm in Trochry. He died on 17th March 1866, in his 85th year. Several newspapers noted the passing of a Waterloo veteran, giving credit to Sir William for both his impulsive action in taking a brother in arms on as his servant when he was discharged without a pension, and providing for his old age. Richard was “much respected by all who knew him and his removal will be deeply regretted in the district in which his more peaceful days were passed.” Murthly had indeed become home, where he had lived for almost two thirds of his life.

Thereafter, now in his seventies, he slipped quietly into retirement. (The photo here is not Richard and Anne, but of a Waterloo veteran and his wife of similar age.) Anne predeceased him. Richard eventually moved to live with his daughter Helen and her husband John Pullar, at their farm in Trochry. He died on 17th March 1866, in his 85th year. Several newspapers noted the passing of a Waterloo veteran, giving credit to Sir William for both his impulsive action in taking a brother in arms on as his servant when he was discharged without a pension, and providing for his old age. Richard was “much respected by all who knew him and his removal will be deeply regretted in the district in which his more peaceful days were passed.” Murthly had indeed become home, where he had lived for almost two thirds of his life.

Sir William lived for another five years.

Sources:

Historical Record of the Fifteenth, or the King's Regiment of Light Dragoons, Hussars by Richard cannon (John W parker, London, 1841)

Quotations from L'Estrange and Joliffe accounts taken from Viscount Sidmouth, a biography by George Pellew (John burray, London, 1847)

Other information on the events of 16th August, 1819, from www.peterloomassacre.org

Richard Ryder's death notice first appeared in the Perthshire Constitutional 22 March 1866. (Repeated in a dozen newspapers across the UK.)

© Murthly History Group