The Reluctant Birlayman

Added on 09 September 2019

Sir John had made them an offer they couldn’t refuse. Even while struggling to find where a flat demand ended, and the offer began...

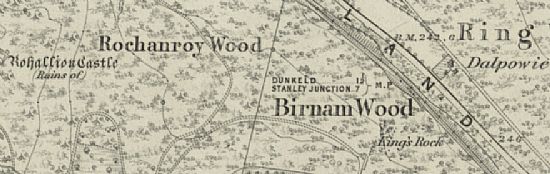

On Saturday 14th March 1789, Thomas Anderson, James and John Bruntfield, tenant farmers across the lands of Dalpowie, met to discuss just how they were going to give in to the laird’s demands. Thomas and James were established Murthly tenants, each on a 19 year lease. (Paying £16 cash money and 6 hens in annual rent.). It is possible that a fourth man was present: James Young, the estate factor. For the short note these men addressed then to Sir John Stewart of Grandtully (1726 - 1797) formally renouncing any claim to the grass and arable land in ‘Roughenroyie Wood’, and acknowledging his absolute right to enclose the wood with a dyke, smacks of dictation. (Rochanroy Wood lies on the lower eastern slope of Birnam Hill, below the ruins of Rohallion ‘Castle’. It was at that time - pre-railway - easily accessible from Dalpowie.)

This may have been the outcome of a negotiated settlement between the laird and three of his better or more reliable tacksmen (of whom, more later). But clearly it was the tenants who stood to lose. For one thing, Anderson was in the last year of his lease. His family had farmed in the shadow of Birnam Hill for over 50 years and, presumably, he was looking for an extension at least. James Bruntfield had doubled his landholding in recent years, having taken on old John McNaughton’s tack when that expired in 1778. Both had more to lose than some common grazing held more by custom than legal right.

The renunciation was written on a scrap of paper. Literally a scrap. Sure, back then paper was expensive, but wouldn’t a formal recognition of the laird’s authority merit at least a full sheet, for filing? Unless Sir John was just making his point: sign here, and we’ll let bygones be bygones.

Except that, after signing resigned acceptance that the new was taking over from the natural order of things (as in ’that’s how we’ve ayewise dunnit’), the men scratched their own PS:

‘Honourable Sir

Above we have Renounced the whole Grafs and arable ground within the Inclofsure you have put around the Rouchenroay Wood or what is intended to be within it and we expect the family will befriend us in time-coming.’

(In other words: it may henceforth be the understorey to your grand new bosky plantation, but it was valuable grazing and cornfields for us and we’ll feel the lack. Please be kind.)

James and John Bruntfield, father and son, appear to have been making a good fist of their doubled acreage as there is no indication of late payments in the rent rolls for this period. We know that Anderson was more than a farmer as he was granted a licence ‘to sell Ales, Beer and other Excisionable liquors’ by the Justices of Peace of Perthshire on the first day of November 1784. As this is but the earliest surviving drinks licence for the area in the Perth archive, there is no reason to suppose that Anderson (then in his 40s) had not been in the business for some years. Trade would have been brisk, as he was living beside or close by what passed for the Great North Road (pre Turnpike) from Perth to Dunkeld, and beyond.

Shortly after this, sometime about 1792, the Rev John Robertson (1737 - 1805), minister of Little Dunkeld parish, was formulating his response to Sir John Sinclair’s call for a statistical account of the nation. (Sinclair had more or less conscripted the clergy of the Church of Scotland into this grand project in 1790. In a round robin to all 938 parishes he set them the same 160 questions on the character of the people, occupations, dress, customs, education, health and well being. Surprisingly, less than a dozen ministers ‘defaulted’.) Robertson noted that ‘the proprietors’, mainly the Duke of Atholl, Stewart of Grandtully, and Stewart of Dalguise, ‘are improving their oak woods by inclosing (sic) them with stone walls, and filling up the vacant spaces with planted oak.’ In particular, he wrote, they were removing birch and ‘other baser wood’. For the good reason that a 24 year old crop of solid oak coppice, unmixed with other trees, covering 300 acres, was then worth £10,000 sterling. On the other hand, the 200 acres of birch woods in the parish were not considered worth more than £2 an acre. Chief among these improving proprietors was John Murray 4th Duke of Atholl (1755 - 1830) who had been at it for over 25 years and had planted up 1,000 acres. However, the owners of Grandtully and Dalguise estates were catching up fast. By Rev. Robertson’s reckoning between them they had planted over a million trees in the past 10 years. The avenue acres and enclosures around Murthly Castle alone must now be worth over £2,000 sterling, he estimated for his report.

(Although the illustration to the left is of an English scene, by Gainsborough, it serves to show what unfenced woodland pasturage would generally have been like pre-enclosures. So alien to the rural landscape we know today. And at least the predominance of birch is authentic.)

(Although the illustration to the left is of an English scene, by Gainsborough, it serves to show what unfenced woodland pasturage would generally have been like pre-enclosures. So alien to the rural landscape we know today. And at least the predominance of birch is authentic.)

Of course, grazing stock and saplings don’t mix; although the good reverend is silent on the implications of this for his parishioners. It is not hard to imagine Anderson and the Bruntfields seeing these plantations gradually spread across the estate, covering if not good arable ground then certainly useful acres, and deciding to make a stand.

The following month James Bruntfield figured on another off-cut of paper. His reward for seeing sense? Perhaps.

‘We George Lauder of Newtyle and James Bruntfield tenant in Dalpowie being picked by Sir John Stewart of Grandtully to be and act in the capacity of Birlay men in Barony of Murthly do hereby accept of the paid office of Birlay men.’

On the same day, two other tenants on the far eastern side of the estate were appointed birlaymen for the Barony of Airntully. They were all to use their experience and influence, acting impartially, when called upon by ‘proper authority’ to do justice between tenants and cottars.

George Lauder’s farm may have lain closer into the castle. The low lying field below present-day Rose Cottage shows on a map of field names across the estate as Newtyle Park. An estate plan of 1825, from before the New Castle was conceived, indicates what may have been farm buildings in that vicinity.

Thomas Anderson’s reward was, presumably, having his tack renewed.

In his excellent one-volume ‘A History of the Scottish People 1560 – 1830’ (Collins, 1969) T.C. Smout describes the function and practice of the ‘Birlay or Boorlaw men’ in rural areas. These were generally experienced, steady tenant farmers appointed by the laird or proprietor in the Lowlands (or from within the community in the Highlands - as on Atholl’s lands on the other side of the Birnam Gap, in Highland Perthshire) to help with the smooth running of an estate. Their function was, largely, to coax and cajole tenants and cottars (labourers) to stick to the ‘rules’ with regard to husbandry: keep head-dykes in good repair, don’t let your animals (be they cows, sheep or chickens) stray into growing crops, and don’t sneak more cattle onto the common grazing than you should. Smout allows that ‘rules’ often meant adherence to blind tradition, and for this reason the birlaymen were already somewhat old hat before the end of the eighteenth century. They were being replaced ‘by a [type of] brisk factor who, being abreast of the new systems of husbandry borrowed from England, told the tenants what they should do without asking their opinion.’ (p126)

Chief among the new systems of husbandry being introduced were the enclosures; the doing away with common grazing.

The story of Thomas Anderson and James Bruntfield’s little rebellion came to light in a small cache of papers relating to local birlaymen among the Grandtully Muniments at the National Records of Scotland in Register House, Edinburgh. (GD121/1/67/408A) An oddly sequenced cache. For here we see birlaymen being appointed after the estate was well started on a process of enclosing what was formerly common grazing.

Change is gonna come. Although for now the traditional system of semi-regulated common grazing would persist (dry stane dyke enclosures are not built overnight). By the early decades of the 19th century, the office of birlayman seems to have been phased out entirely, locally, in favour of land stewards who reported to the factor.