Dalpowie Through Time

Added on 13 May 2019

If we were to put forward a candidate for the next series of BBC2’s excellent ‘A House Through Time’ it would be Dalpowie Lodge, which stood for over 200 years at the western edge of Murthly estate. (Pressed for an alternative we might suggest ‘Dunvorist’ in Station Road.)

Known at various times as The Hospital, Glen Birnam, Dalpowie Lodge, Birnam Hall, and Dalpowie House, it was inked into his will by John Steuart, ‘Old Grantully’, in 1711. He set aside the sum of 20,000 merks (about £1,400 Scots) in the Grandtully Mortification Trust. To provide a small pension for 12 poor and indigent men from his estates of Grandtully, Strathbraan, Murthly and Airntully . . . men ‘of the Episcopal persuasion’, that is. Additionally, he stipulated that two acres of ground, within a mile of the House of Murthly, be set aside for a hospice and garden for them.

So, who was John Steuart? Well, he seems to have been a scholarly bachelor, born around 1643 who, after a reasonably wild youth at St Andrews and in France, returned home to run the family estates. Late in life, years after prudently writing his will and creating an entail for the estates, carefully stipulating which branch of the extended family would inherit when/if any branch failed, he was granted one last fling; and almost given his dearest wish.

For Old Grantully was an unrepentant Jacobite. When James Stuart, seventh of his line, arrived in Dundee in January 1716, en route to Scone and a coronation, John Steuart, then about 73, stood at the Seagate in the biting cold to meet his prince. After all the huzzahs, the cheering and unfettered joy of the citizens (who thus far had been spared any of the privations caused by the rebellion) John spared them further by offering his town house, but a few steps from the Seagate itself, as lodging for the king to be. For which act of fealty he was fined £10,000 sterling by the Hanoverian government, when the rebellion fizzled out and James fled to France, uncrowned.

Old Grantully died in 1720.With one thing and another his dream of a hospice wasn’t realised until 1740. That’s when the Hospital opened. It had a ‘grate Hall', West Room and East Room, Infirmary and Kitchen on the ground floor; upstairs were 12 ‘cells’ for the pensioners, and accommodation for staff. With 18 sash windows it would have been bright and airy. But it never had any inmates. None of the nominated indigents would stay there. They had their family and friends where they lived, and cash money twice a year at Whitsunday and Michaelmas. Why go and live with people they hardly knew, very possibly strangers. (The Steuart lands stretched from the western edge of Stanley to Birnam then all the way west to the outskirts of Aberfeldy.)

The Mortification Trustees met year after year, but the Hospital stayed unused. The laird of Murthly was allowed to rent it out in tack, so long as the revenue went to 'pious causes', and it just became part of the landscape. Early in the 19th century the Murthly factor, James Chalmers, took up residence with his unmarried sisters; a family of servants from the castle lived at the other end of the building, which by then was being called Glen Birnam. When Sir William Drummond Stewart inherited the estates in 1838 he made it quite clear he wanted the building as his private residence. Putting it about that he had vowed never to sleep another night in Murthly Castle ( the consequence of a family feud, apparently) he offered to buy the building and grounds from the Trust. He was allowed to do this in 1844. Whereupon he had the place extensively renovated, furnished with souvenirs from his trip to India, the Grand Tourn through Europe, and his years travelling across the prairies and over the Rockies with the Mountain Men, and renamed Dalpowie Lodge. He then happily lived there for a number of years with his ‘valet’ and constant companion, Antoine.

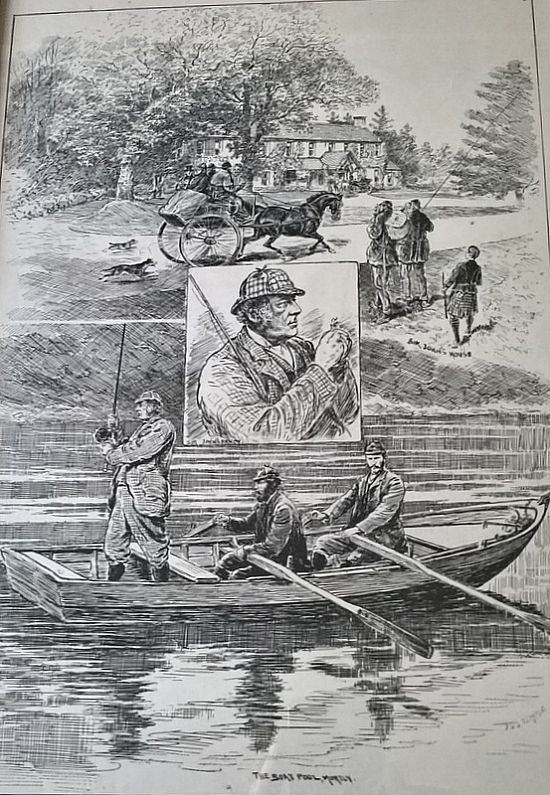

Sir John Everett Millais and his wife Effie Gray had a succession of annual leases from 1882. They benefited from a considerable investment by the estate in renovating the building, creating a large kitchen garden, and building a gated, stepped terrace down to a tennis lawn. The building was lit by gas piped all the way from Birnam. The laird by then was Sir Douglas Stewart, who had a mania for renaming people and places: beginning with himself, as his given name was Archibald; and in a similar vein Murthly had to be known as Murtly; while Dalpowie became Birnam Hall. However named, Birnam Hall became the happiest place on earth for Millais for nearly a decade, where he could shoot, fish, and paint his beloved landscapes away from the day job of renowned Society portrait artist. He was left distraught by the death of Sir Archibald in 1890, or rather its aftermath. For the new laird, Walter Steuart Fothringham, next in line according to Old Grantully’s long entail (drawn up as far back as 1717, remember), reserved the fishing for himself, and Dalpowie for Sir Archibald’s widow, Lady Hester.

Sir John Everett Millais and his wife Effie Gray had a succession of annual leases from 1882. They benefited from a considerable investment by the estate in renovating the building, creating a large kitchen garden, and building a gated, stepped terrace down to a tennis lawn. The building was lit by gas piped all the way from Birnam. The laird by then was Sir Douglas Stewart, who had a mania for renaming people and places: beginning with himself, as his given name was Archibald; and in a similar vein Murthly had to be known as Murtly; while Dalpowie became Birnam Hall. However named, Birnam Hall became the happiest place on earth for Millais for nearly a decade, where he could shoot, fish, and paint his beloved landscapes away from the day job of renowned Society portrait artist. He was left distraught by the death of Sir Archibald in 1890, or rather its aftermath. For the new laird, Walter Steuart Fothringham, next in line according to Old Grantully’s long entail (drawn up as far back as 1717, remember), reserved the fishing for himself, and Dalpowie for Sir Archibald’s widow, Lady Hester.

Eventually, Lady Hester moved to Grandtully Castle and the estate got Dalpowie back into the lucrative shooting and fishing lets cycle. Into a portfolio with its other major sites – Rohallion, Drumour (for a time a refuge for Duleep Singh deposed king of the Sikhs, known locally as The Black Prince of Perthshire) and Loch Kennard. The estate did not scruple to use the Millais connection, even fibbing about some of his landscapes having been painted as if of a view from within the lodge. There was a succession of interesting clients who were either monied, noble, or richly noble.

All of this was interrupted by the first World War. Mrs Steuart Fothringham personally supervised and financed the lodge being turned into a 35 bed hospital in 1917. One of 16 Volunteer Auxiliary Hospitals across Perthshire. So much changed after 1918, however. Sure, there still was Big Money around going into the 1920s, but the middle market seemed to slump. Leasing Murthly and Grandtully castles – to Sir John Mullens, ‘the King’s stockbroker’, and Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Beaty, was no problem. A decent length of rent for the smaller lodges, particularly when the fixtures and fittings were beginning to look a teensy bit shabby? Well, the estate took what it could get.

Vernon Roberts and family leased Dalpowie House, annually, from 1921 - 29. For ever threatening to leave, Mr Roberts more than once missed the deadline for giving notice of quitting, thereby committing himself for another season. Each notice period, Mrs Vernon had to be polite to occasional visitors scoping the premises before committing themselves to a lease, only to find that Vernon had changed his mind and signed for another year. Eventually this pantomime proved too much for her nerves and she persuaded her husband she was now much too ill to continue living there.

Thereafter, the estate seemed to give up on Dalpowie, reluctant to invest enough to restore it to its full pomp when the supply of people willing and able to rent anywhere for several months shooting and fishing was drying up. It had been more or less mothballed when the Royal Engineers forced open the doors and marched in.

That was in 1940. Dunkirk was in the past and invasion was our immediate future. The first question was, where would Hitler strike? The second, how long have we got? Engineers, sappers, and a small army of unemployed, but as yet unconscripted men were furiously digging anti-tank trenches, erecting pill boxes, creating a barrier all the way from the Firth of Forth to Loch Rannoch.

When invasion panic subsided the military left, but someone in command remembered that quiet secluded heavily wooded estate. One well served by the Highland railway. The War Department formally requisitioned Dalpowie House, the New Castle, Malakoff Arch and a number of smaller buildings and cottages in 1943. And set about creating over 200 munitions stores and bomb dumps throughout the wooded policies. Polish troops, many of them billeted in Dalpowie, carried out most of the guard duties.

Dalpowie was returned to the estate in 1946, along with £570 17/2d for ‘damage and deficiencies’. However, restoring the building could not be a priority. Building materials were rationed and there was a real urgency about bringing estate workers’ cottages up to a tolerable standard. In 1951, the factor negotiated its sale for re-useable stone with MH Young of Pitlochry, along with the New Castle and the Arch. The stone was to be reused in cottages for Hydro Electric Board workers in Pitlochry and Tarbert.

The foundational ruins of Dalpowie were further obliterated in the 1970s when the ‘new’ A9 went through the Birnam Gap. All that remain are a large ‘icehouse’, the ruins of a small cottage, and the (heavily over-grown) garden. These are now the focus of continuing surveys under Archaeology Scotland’s ‘Adopt a Monument Scheme’.

The foundational ruins of Dalpowie were further obliterated in the 1970s when the ‘new’ A9 went through the Birnam Gap. All that remain are a large ‘icehouse’, the ruins of a small cottage, and the (heavily over-grown) garden. These are now the focus of continuing surveys under Archaeology Scotland’s ‘Adopt a Monument Scheme’.