The Importance of Being Archibald

Added on 21 May 2019

Being a short account of Murthly’s part in the notorious Douglas Cause, the greatest civil trial affecting status Scotland has ever seen.

Archibald was one of the recurring Christian names of the Steuarts/Stewarts of Murthly and Grandtully. Generally given to younger sons, not first-born. While any Steuart could be on to m'learned friends at the drop of a tilted wig, Archibalds tested the legal process to the max, with major litigations, in the 18th and 19th centuries. Each failed at the Court of Session in Edinburgh but then went all the way to the House of Lords on appeal.

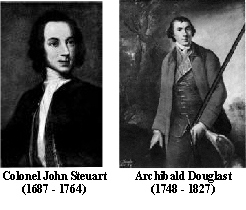

It is doubtful that the 18th century Archibald ever visited Murthly. He and his twin brother Sholto were born in 1748, in Paris, to Colonel John Steuart (60) and Lady Jane Douglas (50), who had married privately two years earlier. The Colonel was the proverbial second son, sent out to make his own way in the world as a soldier. Lady Jane, however, was sister to the Duke of Douglas, one of the richest , most powerful landowners in Scotland. Sister and heir, as the Duke was a confirmed bachelor. Were she not to have married and borne children next in line was the Duke of Hamilton. In light of what subsequently happened, in which Jane’s whole biography was reduced to ‘did she or didn’t she’, history failed her, was neither kind nor fair to one of the more remarkable Scottish women of the 18th century.

Hanoverian to the core, Douglas was never likely to take to a known Jacobite, out for the Old Pretender in 1715. Although Colonel Steuart was considered still handsome - ‘well looked’ in one description – and heir to the estate of Grandtully and a baronetcy, he was already a widower with one surviving son, Jack Steuart. He was known, forby, as thoughtless and inconsiderate to a high degree; also poor, being ‘extremely profuse’ at the card table; and a supposed Papist. Although esteemed by his acquaintances as a man of honour.

With the cats out of the bag, Lady Jane set about breaking the news gently to her brother, using well placed intermediaries and carefully worded letters. (Fancy having to address your brother as 'Your Grace', even in the most private correspondence.) By way of reply the Duke simply cancelled the £300 per annum he had settled on her some years before, and gave Lady Hamilton to understand he would not be best pleased if she were to accept Lady Jane socially. The immediate result was penury for both Jane and the Colonel, who was overwhelmed with debts of the gambling kind and clapped in jail by his creditors.

The Hamiltons and their clique set to work further undermining Lady Jane's position. Was she actually married? After all, didn't she continue to circulate in Society as a Douglas. And twins? At 50! Conveniently far away in Paris? Pull the other one, ma cherie; it plays Frere Jacques.

Malicious aspersions. Innuendo. Generally, talking out the back of an aristocratic hand, gloved or not. Without making accusations (those would come later, in court) the Hamiltons continued to poison Lady Jane's reputation. She died in 1753. Nevertheless, Douglas was reconciled with his nephew before dying in 1768. Which came about in a very surprising manner. The Duke, who had long seemed beyond the grasp of mothers with nubile daughters, suddenly married Margaret Douglas of Mains. The new Duchess took young Archibald’s part, and gradually warmed up her husband so that a rapprochement was made and he was named heir to the extensive Douglas estates. Everything but the dukedom, which could only be passed down through the male line. (Sholto had barely made it out of infancy before succumbing to a fever.)

With so much land and a tidy fortune at stake, the Hamiltons wouldn't let it lie and took to the courts to dispute Archibald's right to inherit, claiming he was a 'suppostitious child'. Colonel Steuart attempted to defuse matters in a testament given just a day or so before his death in June 1764. (By then he was Sir John Steuart, Bart.) In it he confirmed his marriage to Lady Jane and the legitimacy of their two sons. Something he felt compelled to do since ‘aspersions have been thrown out by interested and most malicious people.’ This statement was witnessed by James Bisset, Minister of the Gospel at Caputh, James Hill, Minister at Gourdie, John Stewart of Dalguise, Esq., JP, and Joseph Anderson, ground-officer at Sloganholm on Murthly estate.

The Hamiltons’ case was contested on Archibald’s behalf by the Duchess (technically, he was still a minor) resulting in one of the most expensive litigations before Scotland's Court of Session. The whole of Scotland, and a good part of the English gentry it seemed, were fixated on the trial, and it is said bets amounting to £10,000 were wagered on the outcome. James Boswell and Dr Johnson were among those caught up in fervent speculation. Typically, Boswell both aired his opinions, and tried to turn a coin from them by writing a lightly fictionalised account of Archibald’s supposed origins; Dorando, a Spanish Tale. Which was so near the knuckle it saw his publishers hauled into the dock charged with contempt of court.

The Hamiltons’ case was contested on Archibald’s behalf by the Duchess (technically, he was still a minor) resulting in one of the most expensive litigations before Scotland's Court of Session. The whole of Scotland, and a good part of the English gentry it seemed, were fixated on the trial, and it is said bets amounting to £10,000 were wagered on the outcome. James Boswell and Dr Johnson were among those caught up in fervent speculation. Typically, Boswell both aired his opinions, and tried to turn a coin from them by writing a lightly fictionalised account of Archibald’s supposed origins; Dorando, a Spanish Tale. Which was so near the knuckle it saw his publishers hauled into the dock charged with contempt of court.

In the end their lordships were evenly split. Seven accepted the Hamilton contention that Archibald was neither a Steuart nor a Douglas but a Parisian urchin, one of two bought in some baby market in Rue des Orphelins by Lady Jane for the explicit purpose of bilking her brother. Seven found for Archibald as being the first child of a rather mature mother. So it fell to the Lord President, Robert Dundas of Anniston to break the deadlock: He found for the contention. To much public consternation. Dr Johnson was not the only one who thought, ‘ a more dubious determination of any question cannot be imagined.’

Archibald had a right of appeal to the House of Lords, however, and the judgement of Edinburgh was eventually overturned in London, in February 1769. On this occasion the Scottish public vociferously, ferociously agreed with their Lordships. When the news of a win for the Douglas Cause (as it had become) arrived in Edinburgh a mob assembled, and after parading the streets for some time, proceeded to commit ‘several outrages’ on the houses of the principle gentlemen of the Court of Session. While the rioters were throwing stones at windows, and before regular troops were sent down from the castle to assist the town guard, one gentleman observed, ‘Aye, aye, these honest fellows are giving their casting votes . . .’

Archibald came into his majority and decided on a career in politics, becoming MP for Forfarshire in 1782, and in due course was entitled after all, as 1st Baron Douglas. (He was reportedly disappointed, having expected an earldom.) His elder brother, John, from the Colonel's first marriage, became the 4th Baronet of Murthly & Grandtully, but there is no record of him ever entertaining Archibald at Murthly Castle.

Much has been written about this case. One of the best, even handed accounts is: The Douglas Cause edited by A. Francis Steuart, Advocate (William Hodge & Company, Edinburgh 1909).

More recently, Karl Sabbagh produced The Trials of Lady Jane Douglas (Skyscraper, 2014) in which he reveals fresh ‘evidence’. A letter that Lady Jane may have written, which might be construed as pleading for God's mercy, for . . .

The second Archibald to be involved in a major Court of Session action carried on appeal to the House of Lords was Sir Archibald Douglas Stewart (1807 – 1890). Again, it was a matter of inheritance and whether a marriage did or did not take place. Which will be covered in a future post . . .