The One With Jesuistes and Blackmail

Added on 10 March 2020

Sword or rosary? Edged weapons or prayers? Stark options for Catholics in 1560s Scotland. The Reformation Parliament of 1560 had finally, irrevocably broken with the Holy Father in Rome and was hell-bent on stuffing their religion down History's stank. Their queen, Mary Stuart, held her throne like a cloak clings to a shoogly peg. . .

Five Perthshire pals weighed how best to pitch in. Three were cousins, Edmund Hay of Megginch, William Crichton of Meigle, and Robert Abercromby of Murthly; along with their friends, James Tyrie and William Murdoch, all had graduated from St Andrews. They chose to join the Jesuits and become 'soldiers of God'.

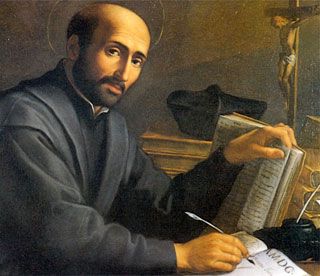

The Society of Jesus was founded by former soldier, Ignatius de Loyola in 1540. Members are not always ordained as priests, but all take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience - in the latter regard particularly to the Pope. As ‘soldiers of God’ they are especially concerned with the defence and propagation of the faith. Jesuits are known for their discipline, training, rigour and intellectual achievements. When the Reformation Parliament outlawed the Catholic religion, Jesuits would spearhead a push-back, the Counter-Reformation. Although the modern image of Jesuits is that of the ‘Black Robes’ they had no uniformity of look then. Indeed, one of the charges levelled against them in anti-'Jesuiste' propaganda of the time was that they dressed and looked like ordinary folk. And operated under aliases: Robert Abercromby, for example, was variously Robert Sandiesoun and Sanders Robertson.

The Society of Jesus was founded by former soldier, Ignatius de Loyola in 1540. Members are not always ordained as priests, but all take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience - in the latter regard particularly to the Pope. As ‘soldiers of God’ they are especially concerned with the defence and propagation of the faith. Jesuits are known for their discipline, training, rigour and intellectual achievements. When the Reformation Parliament outlawed the Catholic religion, Jesuits would spearhead a push-back, the Counter-Reformation. Although the modern image of Jesuits is that of the ‘Black Robes’ they had no uniformity of look then. Indeed, one of the charges levelled against them in anti-'Jesuiste' propaganda of the time was that they dressed and looked like ordinary folk. And operated under aliases: Robert Abercromby, for example, was variously Robert Sandiesoun and Sanders Robertson.

In 1563, Robert Abercromby was admitted into the Society as a lay brother at its Rome headquarters. Ordained in 1565, he spent many years teaching at the Jesuit seminary in Braunsberg (then in eastern Prussia, now Poland) eventually dying there in 1613, aged 77. However, Braunsberg merely bookends a remarkable middle age, much of it spent in Scotland. Mostly in hiding, in fear for his life, although for several years hiding successfully in plain sight.

He first returned home in 1580, aged 44, sailing up the Tay to hide out with his grandfather at Megginch Castle until he got his bearings. Perhaps disembarking at Port Allen, below Errol, although today’s neat little stone pier is of a later date. (The Harbour of Errol only received its charter in 1662.) We don’t know if he got home to Murthly but he was only in the country for six weeks, on a fact-finding mission. During this time he managed to gain three secret audiences with the young James VI. And came away with an overly optimistic view of the young monarch which he passed on to his superiors. Abercromby described James as being secretly in favour of the Catholic cause. ‘ I do not doubt that, if he had a good instructor, he would become in a year an excellent and devout Catholic Prince.’ He did however have the good sense to add that James’ conversion was unlikely in the short term. Abercromby’s critics blame him for being over-sanguine in his hopes of converting the king, and over-reliant on the good faith of the nobility. What he, and other Catholics later on, failed to take into account was that James was an inveterate trimmer, constantly twitching his sails to catch any breeze that would bring him closer to his main goal in life. Mixing metaphors, James’ sole ambition was to be cock o’ the biggest midden, and crow from the throne of England.

Abercromby’s second mission was in 1588, with a fellow Jesuit, William Ogilvie. Both men had immediately to go into hiding while ministering to scattered Catholic congregations. Over the next ten years or so Abercromby converted a number of high-born Scots, including James Lindsay, brother of the Earl of Crawford. These conversions came to the attention of Queen Anne, who had been considerably annoyed that John Lering, the chaplain assigned by her father, Frederick II of Denmark, when she left home at the age of 14 to marry King James, had become a Calvinist soon after they arrived in Scotland.

Anne considered herself deserted spiritually, for she detested Calvinism, and actually asked some Catholic nobles for advice. Speak to Father Robert, they said. (It may also be significant that one of Anne’s maids was called Barbara Abercromby, although I have not been able to trace a definite family connection.) Thus Abercromby was brought into the palace and began instructing the queen in the Catholic religion.

Anne considered herself deserted spiritually, for she detested Calvinism, and actually asked some Catholic nobles for advice. Speak to Father Robert, they said. (It may also be significant that one of Anne’s maids was called Barbara Abercromby, although I have not been able to trace a definite family connection.) Thus Abercromby was brought into the palace and began instructing the queen in the Catholic religion.

Anne was eventually baptised in 1600. Secretly, but with James’ knowledge and tacit consent. Abercromby makes this clear in one of his reports:’ She (Anne) admitted to the King she had dealings with a Catholic priest and named me, an old cripple.’ James went further; so that Anne could have close contact with her Jesuit confessor he appointed Abercromby ‘Keeper of His Majesty’s Hawks’. Father Abercromby SJ thus remained at court, hiding in plain sight, until James and Anne left for London, to be crowned King and Queen of Great Britain in 1603. He operated as the queen’s chaplain, secretly celebrated Mass, and gave Anne holy communion nine or ten times.

It seems clear from his letters back to Braunsberg that both Father Abercromby and Queen Anne thought, or more likely indulged themselves in thinking, they might persuade James to come out as a Catholic. (He had been baptised in 1566 by Robert Crichton, Bishop of Dunkeld.) While that never happened it is still indisputably the case that a son of Murthly, Father Robert Abercromby SJ, did ensure that a Catholic queen, at least, sat on the throne of England.

Abercromby stayed on mission in Scotland, now Jesuit superior for the country. Without the protection of the court he again had to go into hiding. A bounty of 10,000 crowns was put on his head (an enormous sum for that period, £2,500 Sterling, equivalent to half a million pounds today) but he successfully evaded capture for another three years, although by this time old and very ill. (The symptoms outlined in his reports have been likened to those of Parkinson’s Disease.) Eventually he was slipped out of the country in 1606 and returned to Braunsberg.

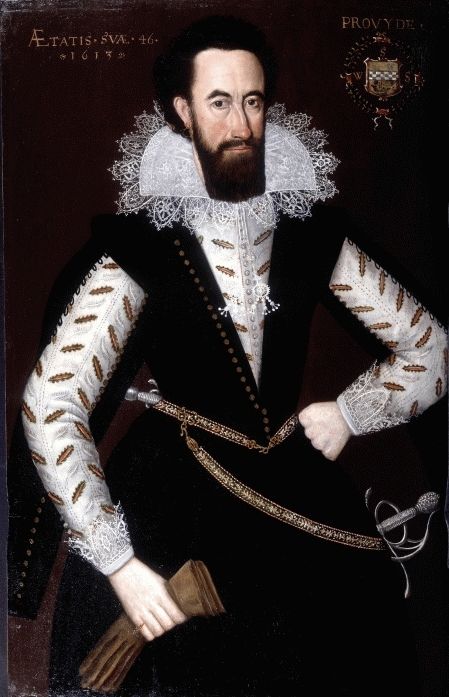

But where did Robert Abercromby and the other Jesuits hide? Some have said they enjoyed relative security on Murthly estate and on Birnam Hill. And this brings us to William Steuart (1567 – 1646) eleventh of Grandtully. He had been the boyhood companion of King James, a page of honour, educated alongside him. And, according to family legend, his whipping boy; the one who took any birching actually deserved by the boy king. Certainly, James acknowledged William’s service several times. For example, in 1585, when he gave him a pension ‘for the gud, trew and thankfull seruice done to us by our wellbelouit William Stewart, our page of honour.’ Typically, this gift of 300 merks Scots annually, was not cash in hand, but had to be uplifted by William from rents raised in the Bishopric of Ross.

But where did Robert Abercromby and the other Jesuits hide? Some have said they enjoyed relative security on Murthly estate and on Birnam Hill. And this brings us to William Steuart (1567 – 1646) eleventh of Grandtully. He had been the boyhood companion of King James, a page of honour, educated alongside him. And, according to family legend, his whipping boy; the one who took any birching actually deserved by the boy king. Certainly, James acknowledged William’s service several times. For example, in 1585, when he gave him a pension ‘for the gud, trew and thankfull seruice done to us by our wellbelouit William Stewart, our page of honour.’ Typically, this gift of 300 merks Scots annually, was not cash in hand, but had to be uplifted by William from rents raised in the Bishopric of Ross.

Whipping boy or not, that’s not the only legend accruing to William. The one that matters more, although difficult to get to the truth of, is how he acquired his nickname, ‘William the Ruthless’. The story goes that he blackmailed the Abercrombies of Murthly into selling him their castle and estate at a fire sale price. If they wouldn’t sell he was going to clype to his friend the king about their harbouring Jesuits. One prominent version of this story was given by Thomas Marshall in Historic Scenes in Perthshire (Edinburgh 1880). It is also mentioned in accounts held by the Stewart Society.

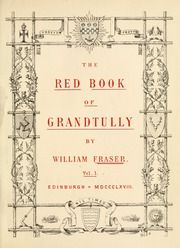

Does the story stand up? The Red Book of Grandtully mentions the purchase. In July 1615 Thomas Abercromby of that Ilk, Alexander Abercromby his eldest son, and others, sold the barony of Murthly for 62,000 merks Scots, or £3,444 8/10d Sterling. Which might be considered a low price, but who knows? For as the ‘Red Book’ puts it, ‘the transfer of large territorial baronies from one family to another was comparatively rare.’ It then goes into great detail about the deed of sale itself; a roll of paper 19’ 4” long and 12” broad. However, in a book mixing extensive Stewart genealogy with odd stories and family legends – one thinks of the long tale of Jemmy the Dwarf here, definitely a blog for another day – there is no mention of Sir William being ‘ruthless’. There is though a small paragraph detailing ‘an old tradition’ that the Abercrombies had attempted to establish a seminary of Jesuits, ‘but the scheme was discovered and abandoned shortly before (they) sold Murthly to Sir William Steuart.’ Is this a cheeky hint, or what?

Does the story stand up? The Red Book of Grandtully mentions the purchase. In July 1615 Thomas Abercromby of that Ilk, Alexander Abercromby his eldest son, and others, sold the barony of Murthly for 62,000 merks Scots, or £3,444 8/10d Sterling. Which might be considered a low price, but who knows? For as the ‘Red Book’ puts it, ‘the transfer of large territorial baronies from one family to another was comparatively rare.’ It then goes into great detail about the deed of sale itself; a roll of paper 19’ 4” long and 12” broad. However, in a book mixing extensive Stewart genealogy with odd stories and family legends – one thinks of the long tale of Jemmy the Dwarf here, definitely a blog for another day – there is no mention of Sir William being ‘ruthless’. There is though a small paragraph detailing ‘an old tradition’ that the Abercrombies had attempted to establish a seminary of Jesuits, ‘but the scheme was discovered and abandoned shortly before (they) sold Murthly to Sir William Steuart.’ Is this a cheeky hint, or what?

We know that Father Robert Abercromby SJ was the most prominent Jesuit in Scotland by the early 1600s, the one the authorities wanted so badly they put a huge bounty on his head. And one such an authority would have been Sir William Steuart. Although Abercromby was out of Scotland by 1606 only his associates would have known this, and it may have been some time before the penny dropped and it was accepted he had flown the coop. Maybe to the extent of keeping alive rumours ( for another nine years?) of Jesuits hiding out in the woods of Murthly. After all, the Protestants with their fears amplified by the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605 estimated there might be 20 – 30 Jesuits operating in Scotland alone. In reality there was less than a handful.

Michael Yellowlees, in his study of the Society of Jesus in 16th century Scotland, So Strange a Monster as a Jesuiste, offers no evidence that Father Abercromby returned to Murthly. Actually, he is convinced Abercromby was spirited away to the north east, under the protection of a significant Catholic noble, the Marquis of Huntly. Nor does he reference plans for building a residential training college for the priesthood (i.e. a seminary) anywhere in Scotland. Such an institution would have had to be authorised by the Superior General of the order in Rome; and possibly also require papal approval. Expensive, it would be paid for by . . .? Well, the Catholic nobles, whose stronghold was in the north east, where there are higher hills than that above Birnam, and more secretive glens than you'll find 12 miles north of Perth.

The Abercrombies could not have been attempting anything on this scale, not without express approval from Rome.

However. If you don't get hung up on the word 'seminary' with its residential training college implications, well-staffed, heavily resourced, as Father Abercromby found in Braunsberg or in the Scots College at Douai in northern France, but imagine a simpler start-up . . . then the Abercrombies could have been planning something. Perhaps in memory of Father Robert whose death, after such a long apostolic service, came in 1613.

The first official seminary established in Scotland was at Eilean Ban, the White Island on Loch Morar, near Mallaig, in 1714. A century later than anything the Abercrombies may have been planning, it was still a very humble affair; several small buildings with turf walls, earth floors and a smoke-hole in each heather thatch roof. A residential seminary for just seven boys, with one priest, a graduate of the Scots College at Douai, although not a Jesuit. The family could even have been going for something in between the Eilean Ban model and the kind of ‘schools’ being established across Scotland whereby boys lived and studied in the home of a priest—a school of this type was recorded in Glenlivet in 1699.

Father Abercromby, over the 18 years of his second mission to Scotland, is credited with persuading dozens of Scots lads to follow his example, and head for established seminaries across the continent. For that was then the only way to get a proper education and training for the priesthood with Catholicism proscribed at home.

When guilt or innocence turns on what a single word, 'seminary', may have meant in a particular context over four hundred years ago, in fairness you would have to say the case against Sir William Steuart of blackmailing his cousin Thomas Abercromby is: Not proven.

For those of you raised in a different judicial system it might help to know that a Scottish jury can deliver one of three verdicts: guilty, not guilty, or not proven. In the latter instance this means the jury is not convinced of the innocence of the accused; in fact, they may be morally convinced that the accused is guilty, but do not find the proofs sufficient for a conviction.

SOURCES

Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)

Fraser, William: The Red Book of Grandtully Vol 1 (Edinburgh 1868)

Marshall, Thomas: Historic Scenes in Perthshire (Edinburgh 1880)

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online)

Scottish Catholic Observer (August 14th 2014, P1)

Yellowlees, Michael: So Strange a Monster as a Jesuiste; The Society of Jesus in Sixteenth-Century Scotland (House of Lochar 2003)

© Murthly History Group