Whey? Whoa!

Added on 09 March 2020

You secure a rare 19 year lease on potentially profitable property close by the Great North Road: Yes!

Payment terms are precise to the penny: Ok.

Details of the acreage, buildings and boundaries are . . . decidedly vague: Oh . . .Kay?

But the landlord has a thing about goats: Deal breaker?

The year is 1770. Your lease is for some ground and the chance to build a brewing business in the lands of Dalpowie, parish of Little Dunkeld, close to the road from Perth to Inverness. Goat whey tourism hereabouts is a thing.

You have weighed it up. (By the time a lease is drafted both sides have come to terms, more or less. Few leases from this time display after thoughts, initialled amendments; although yours will be one.) You know every Murthly lease is fuzzy, unfocused as to the measure of land, but tack sharp on payments, due dates and penalties. And it is a seller’s market; lairds call the shots.

Above all, it’s a 19 year renewable-if-you-keep-your-nose-clean lease. Your chance to get ahead. And the laird might change his mind on the goat thing.

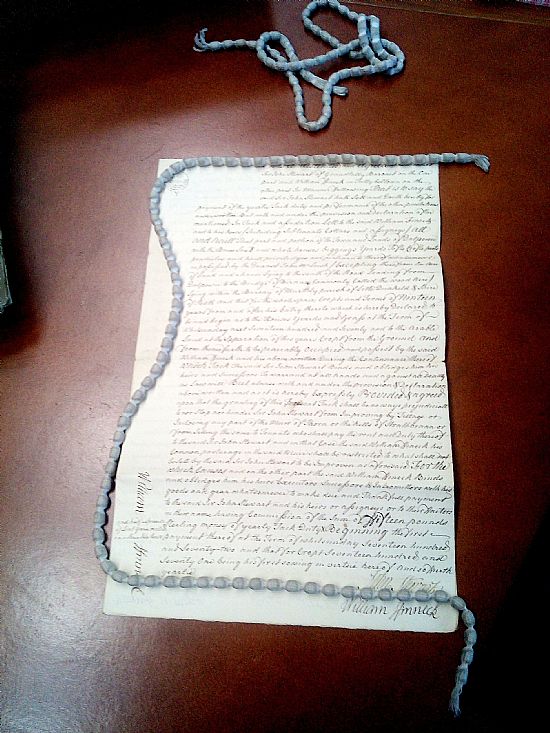

In 1770, William Finnick in Tullybelton (south west of Bankfoot) gets a lease for 19 years in Dalpowie from Sir John Stewart. True to form with Murthly estate leases of this period no measure is given of the rented area; nothing so helpful as its acreage; no specific boundaries. Still less a drawn plan. In common with the other tenants, the annual rent will be paid in a mixture of coin and kain, thirlage, and prestables.

In 1770, William Finnick in Tullybelton (south west of Bankfoot) gets a lease for 19 years in Dalpowie from Sir John Stewart. True to form with Murthly estate leases of this period no measure is given of the rented area; nothing so helpful as its acreage; no specific boundaries. Still less a drawn plan. In common with the other tenants, the annual rent will be paid in a mixture of coin and kain, thirlage, and prestables.

Finnick knows he is taking on ground previously tenanted by John McLeish. That’s actually all the given measure amounts to in writing : ‘a fourth part of the town and lands of Dalpowie previously held by the deceased John McLeish.’ Too bad if you never visited him.

Presumably then, he walked the ground with the factor, Charles Makglashan, before terms were agreed. At this period Makglashan wrote out each lease himself. In triplicate. One going into the estate records, one given to the tenant(s), and one recorded in the Court of Session. Later on he would call on one of his sons, Thomas or Alex, as writer.

Both parties found leases important, increasingly so as the 19 year term became more common. This gave more security to the tenant (and his sub tenants and cottars) encouraging them to invest more time and effort for a greater return. Their importance to a landowner such as Sir John is also clear from several missives in the National Archives where prospective tenants write (or have written for them) the terms they are agreeing to, and accept the then very substantial sum of £2 as penalty if they fail to follow through and sign a stamped, witnessed lease when required. Discouraged time wasters.

Makglashan followed the lawyerly habit of constructing leases around a series of standard phrases. Disconcertingly to the modern eye (legal documents, remember) such a boilerplate phrase was dropped into just about every lease as to the measure of what each tenant was taking on: ‘the houses Biggings yards tofts crofts mosses muirs meadow grazings shealings part pendicles and hail pertinents’. So, ‘presumably’ doesn’t begin to cover it. You would have to be a Holy Fool not to insist on following the factor around, touching everything – house, cottages, barns, fences, pumps, troughs, – noting the size of the manure midden, walking each field right to its head dyke, and all in the presence of your neighbours, the other three fourths tenanting Dalpowie. So they know you know what’s what. No use pointing to this lease in an argument and saying, ‘I think you’ll see it’s written here that my boundary is actually over there.’ If called upon to combat the natural inclination to put one over the incomer from another parish (Tullybelton is in Auchtergaven) in an argument about, say, boundaries or dung heaps.

Finnick’s lease stands out from the others. This isn’t simply an agricultural lease, although arable ground is certainly included. There is more of a business element to it, and a developing one at that. A ‘brew seat’ is mentioned, and he is tasked with building both a kiln and a malt barn. (Sir John to play his part by supplying timber.) His rent is £15 sterling, payable in silver coin, along with a kain of ‘ half a spinnell of lint yard reeled on a three ell reel’. Every lease had annual rent combining coin and kain. The latter, from the Scots word for a hen, was usually just that, an in-kind obligation to make the rent up by providing so many hens each year. As Sir John had more than a hundred tenants across four estates (and was away a lot) each lease also put a monetary value on these hens of 6d. So it was hen or sixpence; ‘in the master’s option’.

Kain was usually two, four, even six hens depending on the size of a farm. But not always. Several tenants agreed to kain of so much spun yarn (presumably from having handloom weavers as cottars or farm workers). Finnick’s agreement to provide linen was actually written as an addition, initialled, in the margin of his lease. Probably a late negotiation rather than an afterthought. Other variations include the miller at nearby Colrie providing two pigs a year, while the lease for commercial salmon fishing on Murthly water carried a kain of 15 fish of no less than 20lbs each.

Thirled is a lovely Scots word or wurd. In its poetic sense meaning bound by the strongest ties of love to a person or place.

As in the second verse of Sheena Blackhall’s poem, ‘The Singing Bird’:

As in the second verse of Sheena Blackhall’s poem, ‘The Singing Bird’:

The mappamound it disna ken

It's thirled tae a rodden tree;

Tethered tae a kenspeckle glen,

'Twad brak its hert tae set it free.

(‘mappamound’ - an old Traveller’s word for the world; ‘rodden’ - Rowan; ‘kenspeckle’ - distinctive, beyond ordinary)

Thirlage is from the same root, but here the ties are of feudal servitude. Although never named as such in any lease, the obligation on every Murthly tenant, from Easter Burnbane to the Obney Hills, to cart ‘all grindable corns’ to Sir John’s two mills at Colrie was exactly thirlage. A hangover from the time when vassals in a feudal barony were thirled to their local mill owned by the feudal superior. Makglashan would often specify in a lease whether the tenant should use the upper or lower mill. Two forms of ‘multure’ were specified: a peck or two of ground oats or grain paid to the miller; and a similar amount to the ground officer (the factor’s man living among the tenants). If any of the tenant’s cottars were also weavers (a lot were, for handloom weaving was a major part of the economy in the district until the end of the century) then their yarn had to be dressed at Sir John’s lint mill. With all three mills fed by the same burn this would have made Colrie one of the busiest areas on the estate.

Other ‘do’s’ or obligations fell under the heading of prestables, and were named as such. Finnick agrees to provide:

One day of his shearers at harvest in parks (enclosed fields) of Murthly;

One day of all his men winning hay;

One day of his men and horses leading hay from Dam of Airntully to the House of Murthly.

This is getting off light. Or rather it suggests his part of Dalpowie does not have much arable ground, indicating the brew seat, kiln and malt barn play the bigger role. As the boilerplate description of a tenant’s holding is so meagre as to be meaningless (‘houses Biggings yards tofts crofts mosses muirs meadow grazings shealings part pendicles and hail pertinents’, remember) it’s the prestables we look to for some idea of size.

By contrast to Finnick, Robert Miller and his sons Andrew, John and David, over in Pittensorn, for example, were obligated to provide 16 men and carts with 32 horses in leading hay from the Dam of Airntully.

So much for the ‘do’s’. Finnick’s lease is notable too for being the only one examined so far (out of hundreds) where the tenant is specifically warned off something: Don’t keep goats or goat whey lodgers. And make sure your cottars don’t either.

The surprising element here is why Sir John had set his face against goat whey tourism. To the point where he forbade a tenant from supplementing his income from something Dunkeld and the local area was known for. There were whey houses in London, where Samuel Pepys noted in his diary they offered a range of whey-based products: whey butter, whey porridge, whey whig (a whey based drink with herbs); and whey borse (broth made with whey). Those benefiting most from this, however, were consumptives, and the further they could get from the foul and smoky stench of London, or Edinburgh or Glasgow for that matter, the better. Somewhere bracingly rural.

The surprising element here is why Sir John had set his face against goat whey tourism. To the point where he forbade a tenant from supplementing his income from something Dunkeld and the local area was known for. There were whey houses in London, where Samuel Pepys noted in his diary they offered a range of whey-based products: whey butter, whey porridge, whey whig (a whey based drink with herbs); and whey borse (broth made with whey). Those benefiting most from this, however, were consumptives, and the further they could get from the foul and smoky stench of London, or Edinburgh or Glasgow for that matter, the better. Somewhere bracingly rural.

One of Sir John’s guests at the castle about this time, Mrs Elizabeth Diggle wrote that,’ People come into this neighbourhood to drink goats’ whey and ride on horseback for their health. Here are pretty good accommodations at a house nearby for such temporary inhabitants & such summer lodgings are advertised in various parts of the Highlands.’ The nearby house may have been at Kinnaird, sadly not Dalpowie. It was regularly advertised in the Caledonian Mercury, an Edinburgh newspaper:

‘There are two houses on the Mains of Kinnaird, to be let this season for Goat-Whey quarters, the one with seven the other with four rooms, beside kitchens and office-houses. For these particulars please enquire of Mr Charles Stewart, at the house Kinnaird.’

Sir John’s mother, Elizabeth Mackenzie, died young. As did his elder brother, George. Perhaps his antipathy was not to the goats but lay in fear of consumption. Today we know the disease as tuberculosis.

We do not know if Finnick saw out his lease. There is a suggestion that Thomas Anderson, who got a 19 year lease in Dalpowie in 1779, took over the brewing. He was given a license to sell alcohol in Dalpowie in the years 1784 – 89, but the records from the Licensing Court in the Perth Archive are incomplete; he may have been a licensee for some years before.